This article is featured on California Voices, a discussion platform that aims to increase public awareness of the state and highlight Californians who are directly affected by policies or their lack. Find out more here.

This passage is taken from Jim Newton’s Here Beside the Rising Tide: Jerry Garcia, the Grateful Dead, and an American Awakening. Copyright 2025.Penguin Random House sells it.

It is common for political and cultural movements to start, flourish for a while, and then face opposition.

Jim Crow can be interpreted as a reaction to the abolition of slavery and civil rights; Roe v. Wade and the Moral Majority; Donald Trump; Barack Obama; and Yes, We Can. Sometimes the backlash comes swiftly, and other times it takes a while. In the case of the 1960s in the United States, the backlash occurred even before the movement recognized itself.

Over the course of 1966, a new thought started to emerge, and an old idea tried—or at least tried—to push the new idea back down.

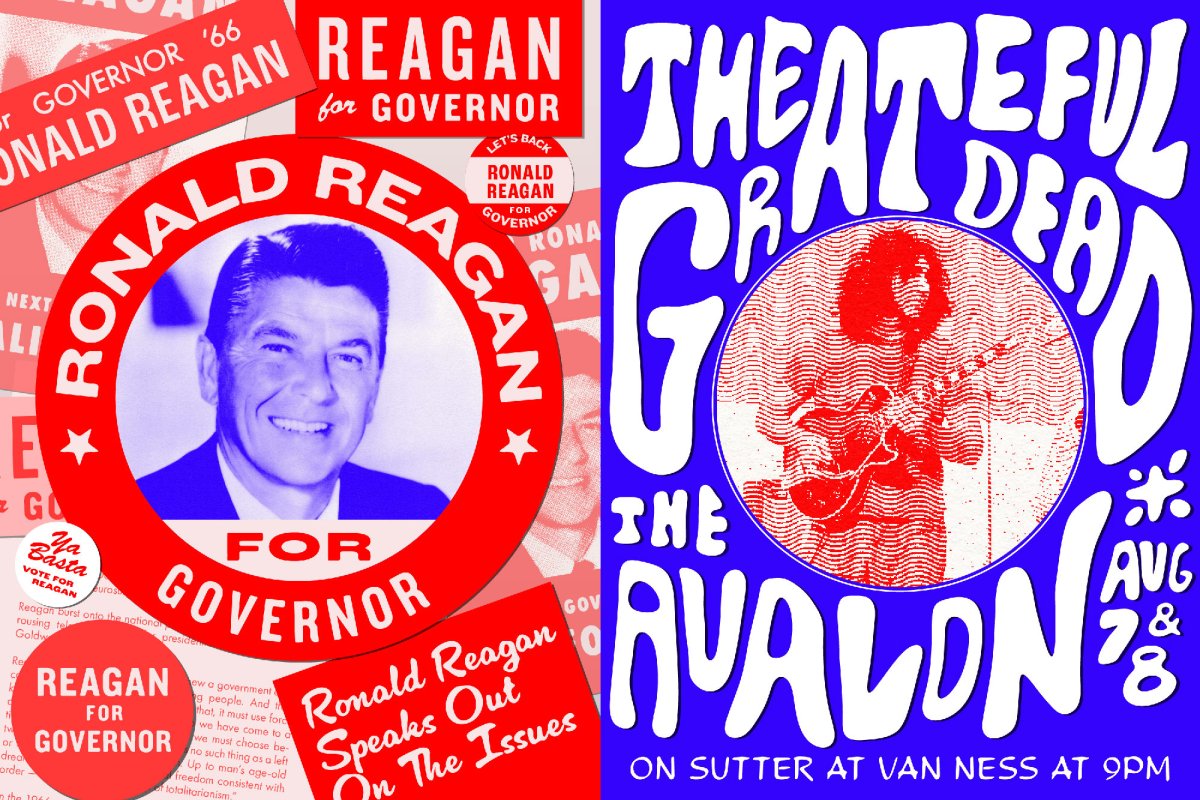

The new ones were the Acid Tests and their descendants. They stood for a variety of concepts, including improvisation and experimentation, politics-centered culture, communalism and joy, drugs, sex, music, and love, as well as restless values rebelling against things they did not yet fully understand. Discomfited adults were the source of the backlash, which centered on Ronald Reagan as the candidate. Reagan ran for governor of California in 1966 as the Acid Tests swept the state. As they vied for supporters, the two campaigns—one spontaneous, the other carefully planned—circled one another.

The Grateful Dead were making a comeback to San Francisco at the beginning of the year. Reagan formally entered the state’s politics after months of touring the area. The movie’s opening banner, Ronald Reagan and A Need for Action!, was first shown to the California press on January 3 and subsequently to the general public on January 4. Although it contained an exclamation point, the presentation that followed was purposefully subdued, a firm request from a comforting guy. Reagan was worried about the state of California, which had historically been a Republican state, only to have that history tested by riots and hippies. Reagan was now also present to restore the status quo and advocate for traditional values.

Pioneers and dreamers, gold panners, and filmmakers were the people of old California. The new California featured drug parties with the Dead, spoiled children at Berkeley, and rioting in Watts.

Reagan embodied conservative ideals. He walked around his gleaming living room, which included brass lights, leather chairs, and a grandfather clock next to a fire in the fireplace. Reagan was calm, firm, and not at all alarmist as he spoke straight into the camera. Reagan never specifically named Pat Brown, even though he was declaring his desire to remove the gregarious and affable incumbent governor of California. He was harsh but never cruel in his criticism of the executive branch.

Reagan’s attitude notably hardened when it came to talking about the state’s children. Reagan pointed out that California had invested money and effort to create a superb institution, but that was insufficient.

With one hand on one of those leather chairs and the other in his pocket, he stated, “It takes more than dollars and stately buildings.” Or do we no longer believe that teaching respect for law and order, self-discipline, and self-respect is necessary? Will we permit a loud, dissident minority to bring down a wonderful university? Will we react weakly and hesitantly to their neurotic vulgarities, or will we tell those in charge of running the university that we expect them to uphold a code of conduct based on decency, common sense, and commitment to the university’s lofty goals? We’ll support them wholeheartedly as long as they do this, and we won’t accept anything less.

This was a favorable political scenario for Reagan. The Berkeley findings were concerning, at least to Reagan’s generation and sensibilities. In some way, radicals had taken root, outwitting their elders in a dispute over what exactly qualified as education and challenging even concepts like freedom and citizenship. Reagan’s main contention was that soft leaders were mishandling California. Parents questioned the taxes they paid to send their children to the best public university system in the country, only to see it turn into a breeding ground for disrespect and disobedience. Reagan recognized it. Knowing that the university was his opponent’s pride, he hammered it.

Reagan had significant political advantages going into the election, particularly in California’s strained racial relations and rising white dissatisfaction with Black calls for justice. The other foundation of the case was the Watts riots of 1965, which are now a hot topic in California politics.

In Watts, a suburb south of downtown Los Angeles, two California Highway Patrol officers stopped 21-year-old Black male Marquette Frye for suspected drunk driving just after 7 p.m. on August 11, 1965, sparking the start of the riots. Not far from Frye’s house, the authorities stopped his vehicle. When Frye’s mother and brother witnessed the officers administering sobriety tests, they vehemently argued in defense of him. When Ronald and Rena Frye were taken into jail by the CHP, the situation deteriorated as a crowd started to form. A thousand people were fighting with police in the streets during the night in a matter of hours.

According to the Los Angeles Times, that was only the start, a prelude to Act I of a horrible catastrophe. As violence erupted from Watts and extended throughout south L.A. over the course of the following two days, 34 individuals lost their lives. Although racism, redlining, police brutality, and the harsh consequences of poverty were all simmering beneath the surface of the riots, subsequent polls revealed that white Americans majority thought irresponsible Black people were responsible for starting and carrying out the riots. A core of white unhappiness was implied by those feelings, which included anger that Black people would turn to violence and resentment that Black people did not value California’s attempts at desegregation.

The emerging counterculture would find common ground with Black activists. Whites would find their way to Reagan, confused and self-righteous.

Reagan was well aware of Brown’s vulnerability in relation to the riots and the Berkeley events. Every mention of the riots was a fresh reminder of the accusation that Brown was absent when it counted, since the university was his most cherished gift to California and he was noticeably absent for Watts, who was on vacation in Greece when the riots started. Reagan’s bigger, albeit hazily subtextual, thesis was that grownups had left the scene and that Black people or teens were acting irrationally.

The Acid Tests were evidence of it. The most complacent parent was unnerved by the sight of young kids high on God knows what, wearing strange clothes, and having long, unclean hair. It brought back memories of Reefer Madness and shady Beatniks. They appeared to be part of the growing sense that something was evaporating, a common dedication to law and order and American ideals. They didn’t think it was nice that anything new was happening. Some people thought it was communism, not because most Americans were familiar with it, but because this new force, this increasing energy, was subversive and menacing, just like communism. The electorate was terrified.

Reagan told them that they had a right to security and that they hadn’t always been afraid. These were the schools where their kids attended. How could they remain still while their own kids disregarded their morals? It was so blatantly incorrect, and they couldn’t possibly be to blame. They paid for the social programs designed to demonstrate their concern for Black people, who now rioted in retaliation, and they worked hard to create the colleges that now challenged their intellectual dominance. Dare they?

Reagan reassured them that he would handle the disturbance and that it was not their fault, that it was being caused by other drug traffickers, well-meaning but misguided leaders, and yes, even communists.

The globe, and California in particular, was undergoing rapid change in 1966. In fact, the transformation was evident in San Francisco’s streets at venues like the Avalon Ballroom and the Fillmore.

Jerry Garcia responded with what appeared to be indifference as Reagan hounded Pat Brown. Reagan condemned drugs and youthful misfits; Garcia and the Dead, who were every bit the misfits Reagan portrayed them as, performed and dropped acid. They traveled up and down the coast during the winter and spring of 1966, circling Reagan’s campaign while disregarding the candidate’s challenge to all they believed in.

As has frequently been said, the Dead were not political—at least not in the way that we typically think of politics. They didn’t support Pat Brown or show up at his events. They didn’t strive to get young people to vote or generate money for candidates.

However, that is an excessively limited definition of politics. By definition, they were political times. Politics and culture whirled together. It was political to get high. It was political to dance. Importantly, an Acid Test was an act of disobedience as much as a joyful and experimental evening. The conflict of ideals and lifestyles was at the heart of California politics in 1966, if politics is to be understood as protest in its broadest sense.

The world, and California in particular, was changing rapidly in 1966, according to a letter written by the Merry Pranksters’ buddy Robert Stone. In fact, the transformation was evident in San Francisco’s streets at venues like the Avalon Ballroom and the Fillmore. At a wisecrack, political and social structures fell apart because they lacked confidence and a sense of humor.

Was the Trips Festival just a joke?

READ more from jim newton

Los Angeles needs civic leaders right now. All it has are political ones

I m in one of his TV shows : The federal government is staging political theater in Los Angeles

CalMatters has further information.

Text

Receive breaking news on your mobile device.

Get it here

Use our app to stay up to date.

Register

Get free updates delivered straight to your inbox.

Nonpartisan, independent California news for all

CalMatters is your impartial, nonprofit news source.

Our goal remains crucial, and our journalists are here to empower you.

-

We are independent and nonpartisan.

Our trustworthy journalism is free from partisan politics, free from corporate influence and actually free for all Californians. -

We are focused on California issues.

From the environment to homelessness, economy and more, we publish the unfettered truth to keep you informed. -

We hold people in power accountable.

We probe and reveal the actions and inactions of powerful people and institutions, and the consequences that follow.

However, without the help of readers like you, we are unable to continue.

Give what you can now, please. Every gift makes a difference.

With Kamala Harris out, who will emerge as frontrunner in California governor’s race?